Plight of the Migrant Labourers Through the Lens of Lockdown

Guest column: Soumya Chattopadhyay

This article first appeared in the Uttarbanga Songbad. The article is reproduced here with the author’s permission.

Migrant labourers! This phrase must have been engraved in our collective psyche in the current conundrum, perhaps to the same degree as the terms Corona and Lockdown. There can be debate regarding which segment of the working class as a whole is being classified as the Migrant Labour force, but we will let that slide for now. Migrant labourers, as a community, had largely been invisible in the eyes of the upper echelons till the recent past. In these exceptional times, their plights have, at last, entered the privileged drawing rooms. Just ten weeks back, greater social conscience had largely been deaf to their issues. And we are here, consuming their ‘stories’- in print, on our Facebook timelines, on our TV screens. The sheer helplessness, bawling cries asking mercy, the despondent gaze of hunger, the ghastly sight of mangled remains of a party that had set out on a long journey home, the image of a toddler tugging his deceased mother’s clothes in Muzaffarpur railway station, and so on. Countless such images have been etched on our brain, possibly for a long time to come. The pressing question is, however, although they seem to belong to a realm, faraway from ours, in the real world, are they that removed from our physical space? Do they seem to ply only in the space of news or social media? If we look minutely, they happen to be the same young adults from our urban locality who had completed their Polytechnic or Nursing degrees, our schoolmates from the suburbs, or our neighbours from our native villages, who all had to flock outside of their respective state all over the country for opportunities. Some are part of the thriving textile industry in Gujarat, some are employed in the construction of swanky civil projects in Tamil Nadu, some work as a supervisor, or skilled labour in a factory in Maharashtra, some don the dress of a nurse in a super-speciality hospital in Bengaluru. What had exactly led to this juncture, where their collective plights have been laid in their bare forms? In reality, this is not a sudden occurrence. The lockdown crisis has managed to draw our attention to even a more deeply-rooted crisis, albeit for a brief moment.

Let us state some experiences of our own. In the early days of the lockdown, we had started a 24-hour helpline in six Indian languages. The purpose was to document the groups of labourers who have been stuck in various parts of the country. In the early days, the complaints that came in were mainly concerned with issues of food, housing, and wages. In each case, the local authority had been primarily contacted, since, as per the government directive, it was the host state’s responsibility to mitigate these issues. But the reality was disheartening, to say the least. In order to ensure that a migrant labourer be provided with the basic amenities, viz., ration and housing, in addition to monitoring proper payment of wages, the respective host states are supposed to maintain the necessary records. Instead, even the bare minimum records did not exist, the absence of which meant, the much-vaunted declarations had been rendered moot.

There had been sporadic instances where help-groups have urged local administrations to provide one-time relief to groups of labourers who have been stuck. Community kitchens have been set up in many places under the aegis of local administration. But barring a few exceptions, the supply of rations has not been regularised anywhere. Even in the case of the functional community kitchens, the quantity and quality of the food served is not suitable for consuming day in and day out. Due to the inadequacy of Government efforts to provide timely support, it came upon the various civil society groups to provide emergency relief to the stranded labourers.

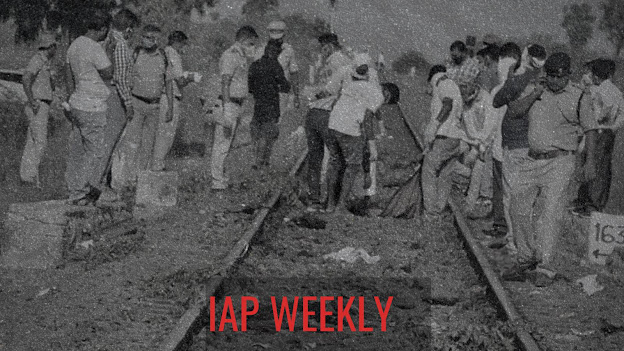

At the onset of Lockdown 2.0, the stranded labourers themselves had been vocal about returning home. The Central Government had been pressurised by political forces, labour unions, and the citizens themselves, to lay out a proper policy for the return of the migrant labourers. After much dithering, the Government mouthed a slew of measures. A series of Shramik Special Trains were announced whose modalities were laid out in convoluted terms. The hiked fares for the announced trains were to be borne by either the stranded labourers or by the respective state governments. An online portal was started to register the names of labourers stranded in various states, a process which was complicated in the first place and largely inaccessible. On top of all these issues, the corruption racket which included local police and administration raised its ugly head. In this conundrum, scores of stranded labourers had started walking for their native places with their lives on the line, a story which is playing itself out repeatedly for too long in this pandemonium. Some have cycled for thousands of miles; some have burnt through their hard-earned cash meant for their family for a head-space in overcrowded buses and trucks headed for their hometowns. A significant delay was incurred to safeguard the interests of the corporate lobbies whose engines are kept running by this vast body of migrant workers.

For the chosen few who managed to board the home-way bound trains, a different saga of woes unfolds. The meal provided is paltry, which is at times inedible as well, and insufficient drinking water during the uncertain indefinite journey makes the ordeal gut-wrenching. After infinite suffering, the migrants manage to return towards their nest, spent, exhausted from hunger and thirst, with a broken spirit and health. The media has reported 80 deaths in the first 19 days of operation of these trains. A new ordeal awaits them after deboarding. Quarantine and screening facilities are often absent in their native places, and fearing infection, the villagers refuse to let the migrant workers enter their villages.

In midst of all this glum, some slivers of a silver lining have gleamed here and there. A few pictures, other than that of despair have emerged. There have been reports of more than 170 demonstrations organised by the labourers across the country since the beginning of the lockdown in demand of ration, housing, regularised wages, and in protest of excesses by the police and employers. This indicates labourers are not consenting to the state-sanctioned status-quo and are standing up for their rights. Another aspect of the whole conundrum is striking. In managing the whole pandemic situation, the state only depended on the bureaucracy at the helm. The whole body of elected representatives essentially acted as a bystander. The farce, orchestrated by the world's largest democracy, is hard to digest

The capitalistic system already entailed forced migration of masses in search of economic opportunities. But over the last three decades, globalisation and economic (neo-)liberalisation have led to a massive paradigm shift in how the migrant labour force is mobilised across the globe as well as in India. This has led to a significant change in the migration pattern of labourers. A vast majority of the labour force is employed in the informal sector, which has stripped this section of the rights as mandated under labour laws. Often, the adequate social security benefits fail to scale the barrier of apathy and mismanagement of the Labour Ministry to reach the informal sector Due to the transient nature of their employment, the interests of this corpus of the migrant labour force are of no one’s headache in particular. This force is peripatetic, so their abode shifts from time to time. As a result, their influence on the local socio-political fabric of their place of settling, for the time being, is negligible. So, their transience is primarily responsible for their insignificance in any discourse. The Central Ordinance of 1979 regarding migrant labourers often fails this informal sector. State Governments have no comprehensive real-time data on the intra and inter-state migrants. In the garb of Labour Law Revision, the various hard-earned rights and privileges of labourers are being taken away one by one. On the other hand, we have this vast community of unheeded migrant labourers, who by their very fate and by design are unprotected in the face of exploitation. A major task in the coming days will be to stage a wide-spread organised movement in our country to ascertain the rights of migrant labourers.

The author is associated with the Migrant Workers’ Solidarity Network (MWSN).

This article first appeared in the Uttarbanga Songbad. The article is reproduced here with the author’s permission.

Maharashtra govt has just told groups working with migrant workers who want to go home that it will still run Shramik trains, be in phone contact with them and try not to insist on documents. But apparently they need 1200 passengers before running a train. Still struggling with the issue.

ReplyDelete